What is 1,4-Dioxane?

1,4-dioxane is a synthetic industrial chemical that mixes completely in water. It persists for a very long time in the environment and is associated with many health risks. Manufacturers often use it as a solvent to create other chemicals like those found in cosmetics, detergents, shampoos, paint strippers, glues, pesticides, medicines and foods. It is also used in the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals and is a byproduct in the production of certain plastic containers.

1,4-Dioxane and your health

The EPA suspects 1,4-dioxane may cause cancer when people are exposed to it through air, water, or by skin contact over time. Short-term exposure effects include eye and nose irritation. Other long-term exposure effects may include liver and kidney damage.

1,4-Dioxane and the Huron River watershed

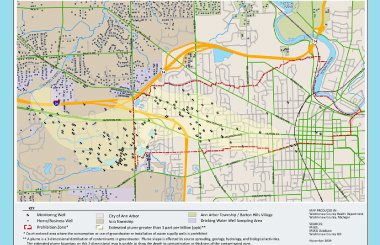

A large 1,4-dioxane plume is spreading beneath western Ann Arbor and Scio Township due to decades of pollution from the Gelman Sciences (now Pall Corp., a division of Danaher Corp.) facility on Wagner Road. A plume is an area underground where the dioxane is moving through soil or water. The plume exists because dioxane does not stick to soil particles, so it can move from soil into groundwater and eventually reach surface water. The plume likely originated around 1966 when Gelman began using dioxane to manufacture various medical and scientific products.

In 1984, University of Michigan Public Health graduate student Dan Bicknell discovered 1,4-dioxane in Third Sister Lake in west Ann Arbor near the Gelman property. By 1985, the Washtenaw County Health Board found the presence of dioxane in 30 water supply wells north of the Gelman property. The state initially sued Gelman in 1988, leading to a 1992 Circuit Court Consent Judgement (a legally-binding court-ordered agreement that has the consent of all the parties in the case), in which Gelman agreed to pay the state over $1 million in damages and begin a $4 million cleanup project.

Gelman has spent years conducting pump-and-treat remediation under court orders, gradually extracting contaminated water from the ground and treating it to remove dioxane the company once dumped into the environment. The treated water with lower levels of dioxane is then discharged to a tributary of Honey Creek, which flows to the Huron River.

Between 1995 and 2000, then Governor Engler and the Michigan State Legislature took a series of actions that increased the allowed level of 1,4-dioxane in residential groundwater from 3 ppb (parts per billion) to 85 ppb―much higher than the EPA’s guideline of 0.35 ppb.

In 2016 traces of 1,4-dioxane were found beneath Waterworks Park in west Ann Arbor. In response, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (now the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy or EGLE) set an emergency standard of 7.2 ppb allowed in residential drinking water. The emergency rule was made permanent in 2017. That same year, HRWC, the City of Ann Arbor, Scio Township and Washtenaw County joined the state’s lawsuit against Gelman to negotiate for a stronger clean up.

In 2019 and 2020, elected officials from the City of Ann Arbor, Scio Township, Ann Arbor Township, and Washtenaw County held forums to discuss the option of pursuing Superfund designation for the dioxane plume , which would place the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in charge of cleanup activities at the site instead of the State of Michigan. HRWC informed these discussions and remains committed to the legal negotiations as the current best way forward. No decision has yet been made by the affected communities to pursue Superfund status.

Scientific monitoring shows that, despite prolonged attempts to mitigate the spread of the of the dioxane plume, it continues to grow, threatening area residents, the river, and the connected ecosystem.

What HRWC is doing

To protect the Huron River, we have taken steps to limit the spread the dioxane plume. In 2016, HRWC the City of Ann Arbor, and Washtenaw County joined the state’s lawsuit against Gelman. HRWC’s motivation for joining the lawsuit was our belief that the river needed a strong advocate and our concern for impacts to the river stemming from a lack of cleanup action. Former Executive Director Laura Rubin said “the city will represent concerns about groundwater contamination and the county’s focus will be well water contamination. But we feel the interests of the river are at risk and that nobody’s representing those.” The dioxane could affect fish and other aquatic life, as well as people, if it gets to our streams or the Huron River itself.

Gelman 1,4-Dioxane Litigation

On August 31, 2020, after years of confidential negotiation, the Washtenaw County Circuit Court partially lifted the confidentiality restriction against disclosure of the negotiations between Gelman Sciences, the State of Michigan and the intervenors (City of Ann Arbor, Scio Township, Washtenaw County and its Health Department, and HRWC). The proposed settlement documents that resulted from these negotiations are now public and can be viewed via a document repository webpage. The repository page includes resources explaining the proposed settlement documents.

The proposed plan, which includes the Fourth Amendment to the 1992 Consent Judgment, Dismissal Order, and Settlement Agreements, were reviewed publicly by residents and elected officials. Many residents and elected officials expressed concerns that the plan does not go far enough. HRWC supported the proposed plan, concluding it is currently the best option overall to protect area residents and the environment.

In 2021, Washtenaw County Circuit Judge Tim Connors ordered that key elements of the new cleanup plan be followed. Some elements of the plan were left for ongoing negotiation. In 2022, Gelman won on appeal, and the 2021 court order was vacated.

Congresswoman Debbie Dingell issued the following statement in response:

“Polluters who do not take responsibility for their toxic waste must be held accountable and our communities must have faith that the judicial system will provide that justice. This ruling overturning the 2021 judicial order that would force Gelman to enact urgent, substantive cleanup measures will put human health and our water at risk. For decades, Gelman has attempted to stall and deflect while the plume spreads and threatens our water and environmental health. It was clear already – and even clearer now – that we must act urgently to designate this site as an EPA Superfund site so that we can finally clean up this site and begin to end this nightmare for families living in this area.”

In response to what would have been additional, ongoing, and constricting legal stipulations from the court, HRWC decided not to remain as an intervenor in the case and instead focused on advocating publicly for a more robust cleanup.

In 2023, the state agreed to a 4th Consent Judgement with Gelman. While an iterative improvement from the previous agreement, the 4th consent judgement highlighted severe weaknesses in polluter accountability laws and EGLE’s enforcement ability.

Consideration of EPA Superfund Status

Citing what they believe to be failures in the state polluter accountability framework, many elected officials, subject matter experts, and community leaders have called on the State of Michigan to request that the Environmental Protection Agency classify the Gelman plume as a federal Superfund site. In April 2021, Governor Whitmer sent a formal letter requesting the EPA reinitiate the assessment and classification process for the Gelman plume. EPA officials have been watching the Gelman plume for years, and in November 2021, selected a firm to begin reassessing the site.

There has been passionate public discussion about whether the state should pursue EPA Superfund designation of the Gelman plume. Those discussions have been complex, but there are key takeaways from EPA officials: The EPA Superfund cleanup process would be thorough but slow. A full EPA cleanup of the Gelman plume will take many years or many decades, depending on what the intended final conditions are for the site.

Proponents of EPA Superfund designation point to a logical distinction between the intent of the current state cleanup and a potential Superfund cleanup process. While the state’s intent is to limit exposure and harm to people and the environment, the EPA aims to return Superfund sites to conditions before contamination occurred, when feasible. (The limitations of what a Superfund cleanup process would provide remain unclear, and a site assessment could help address that uncertainty.) Proponents of sticking with the negotiated state cleanup process point to the need for ongoing and immediate action to limit the spread of the plume. HRWC finds both of these arguments valid.

Quick Links:

Gelman Proposed Settlement Documents Repository Page, includes Consent Judgment proposed fourth amendment and related documents

Gelman 1,4-Dioxane Litigation Page, includes historic timeline and answers to frequently asked questions

News Release, issued August 31, 2020

HRWC’s 2020 statement supporting the Negotiated Cleanup Plan

What you can do

If you are using a well system, you should have your water tested regularly. If you live directly over the plume or near the edge of it, EGLE should have contacted you about doing testing, all you must do is allow it. If you have not been contacted and your well water is not being tested, please contact Jennifer Conn at Washtenaw County Health Department (734) 222-3855 or Dan Hamel at EGLE (517) 780-7832.

If you are connected to the City of Ann Arbor’s water supply, you can read the latest Water Quality Report to find out more about 1,4-dioxane levels.

If you would like to test your water, you are responsible for any cost. See Testing Your Drinking Water for 1,4-Dioxane. There are three laboratories located near our community that you can use.