The negative impacts of dams on rivers

Dams serve a wide range of purposes, such as providing hydroelectric power, water supply, and irrigation, supporting recreation and shipping, and managing flood control. Many dams have become integral to the identity of their communities. Across the United States, 2.5 million dams of all sizes block and harness rivers. Most of them are quite small. Of those 2.5 million dams, only 80,000 are more than six feet high.

Although dams can provide some benefits, dams produce severe negative impacts on the rivers they harness. Dams alter a river’s chemical, physical, and biological processes. Although these negative impacts have become more obvious over the past two decades, the environmental costs of dams have only recently captured scientific attention.

- Dams cause the build-up of sediment. They block free-flowing water and impede the river’s flushing function, as well as the transport of nutrients and sediment downstream.

- Dams fragment rivers and block the natural movement of fish and other aquatic species.

- Dams contribute to, and sometimes are the sole cause of, many species becoming threatened, endangered, or extinct. Prime dam sites often are prime fish spawning sites.

- Dams alter water temperatures, dissolve oxygen levels, and produce turbidity and salinity, both upstream and downstream of the structure.

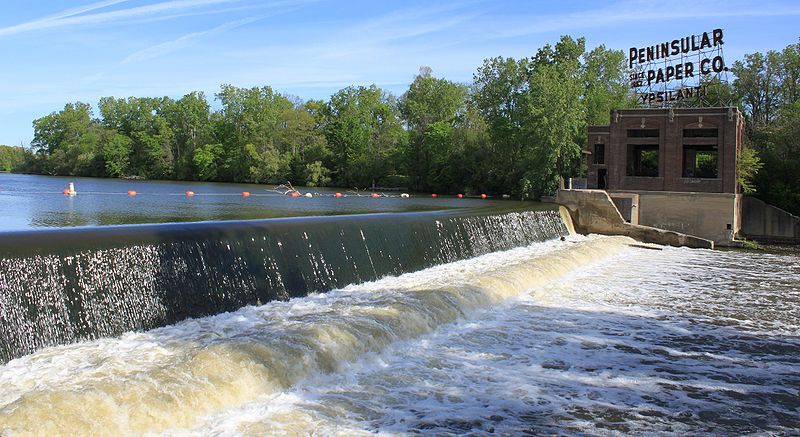

The Huron River Watershed Council and Dams

The Huron River system is typical of rivers and tributaries in the Great Lakes Basin. What was once a free-flowing river system is now interrupted by dams on both the main stem and the tributaries. State and national inventories record 100 dams on the Huron River system.

As the dams in the watershed age and require investment for repairs, an increasing number of communities, dam owners, and government agencies will face decisions on what to do about dams. The decision to remove or rehabilitate a dam involves many considerations, as do the decisions about what methods to use to restore a free-flowing stream. Such considerations include dam safety, environmental impact (i.e. possible toxins in the accumulated sediment behind the dam), and economic issues.

Concerned community leaders and citizens have worked together to remove dams and restore reaches of streams in the watershed (Dexter’s former Mill Pond dam on Mill Creek) and throughout Michigan and the country. In the Huron River watershed, we have the opportunity to:

- restore more than 100 miles of a freshwater ecosystem;

- expand viable habitat for sensitive species including North America’s most endangered animal, freshwater mussels; and

- support local economies in riverfront communities through improved water quality and enhanced recreation opportunities.