The Huron is southeast Michigan’s only “Country-Scenic River,” yet it too faces pollution challenges. Bacterial contamination, especially following rain storms, remains a human health concern for some parts of the watershed.

What is bacterial contamination?

There are many forms of harmful bacteria that can contaminate a watershed. However, only one form of bacteria, E. coli, is measured as an indicator of the presence of bacteria in general.

Coliforms are a group of bacteria that includes a smaller group known as fecal coliforms, which are found in the digestive tract of warm-blooded animals. Their presence in freshwater ecosystems indicates that pollution may have occurred and that other harmful microorganisms may be present. A species of fecal coliform known as Escherichia coli, or E. coli, is analyzed to test for contamination, and its presence may predict the presence of multiple harmful microorganisms.

While most strains of E. coli are not dangerous, some strains and associated microorganisms, when taken into the body, can cause severe sickness.

It is important to note, however, that an elevated level of E. coli in one part of a body of water does not mean that the entire body is contaminated. One key area where HRWC is working to define the scope of the bacteria contamination is Honey Creek. A remediation plan has also been developed for the Huron River between Argo and Geddes Pond impoundments.

Why do bacterial levels matter?

The State of Michigan, through the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, in accordance with the U.S. Clean Water Act, established “designated uses” for the waters of the state. These uses are the targets toward which watershed management policies aim. It is the goal of Michigan residents to attain these designated uses for every water body in Michigan. Included in these designated uses are in-stream recreational uses. Two types of recreational use are designated:

The State of Michigan, through the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, in accordance with the U.S. Clean Water Act, established “designated uses” for the waters of the state. These uses are the targets toward which watershed management policies aim. It is the goal of Michigan residents to attain these designated uses for every water body in Michigan. Included in these designated uses are in-stream recreational uses. Two types of recreational use are designated:

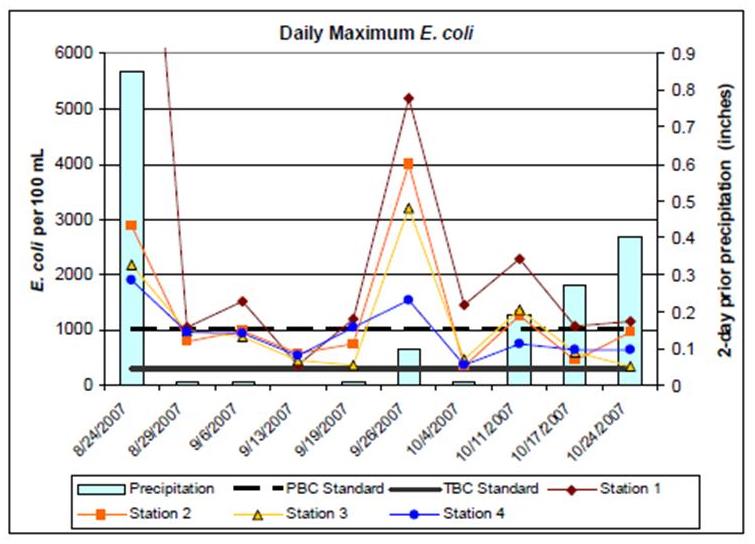

- Year-round partial body contact (PBC) recreation (for example, canoeing, kayaking or wading.) The maximum levels for PBC recreation are “1,000 E. coli per 100 milliliters (mL) [of water].”

- Total body contact (TBC) recreation between May 1 and October 31 (for example, swimming.) The maximum levels for TBC recreation are “130 E. coli per 100 (mL), as a 30-day geometric mean.” In addition, “at no time shall the waters of the state . . . contain more than a maximum of 300 E. coli per 100 mL.”

These levels were established to protect people from contracting illnesses due to contact with waters containing bacteria. Any open water can contain levels of bacteria originating from a variety of sources such as wildlife. Research compiled by the DEQ indicates that, when levels exceed the standards listed above, the likelihood of gastrointestinal illness, such as bacterial infections (cholera, salmonellosis), viral infections (hepatitis, gastroenteritis), or protozoa infections (cryptosporidiosis, giardiasis), increases. Once these pathogens are in a stream or lake, they can infect humans through ingestion, skin contact or contaminated fish. This is not always due directly to E. coli, but high levels of E. coli may be indicative of other human health contaminants.

These levels were established to protect people from contracting illnesses due to contact with waters containing bacteria. Any open water can contain levels of bacteria originating from a variety of sources such as wildlife. Research compiled by the DEQ indicates that, when levels exceed the standards listed above, the likelihood of gastrointestinal illness, such as bacterial infections (cholera, salmonellosis), viral infections (hepatitis, gastroenteritis), or protozoa infections (cryptosporidiosis, giardiasis), increases. Once these pathogens are in a stream or lake, they can infect humans through ingestion, skin contact or contaminated fish. This is not always due directly to E. coli, but high levels of E. coli may be indicative of other human health contaminants.

So, is it safe to swim in the river?

The answer is a little complicated, but along most of the length of the Huron River, it is safe to swim. High bacteria counts have not been detected downstream of Kent Lake all the way to Argo Pond, and then, again downstream of Geddes Pond (Gallup Park) all the way to Lake Erie. The main exception, then is the river running through the Ann Arbor urban area between Argo and Geddes Ponds. Also, bacteria counts rise following rain storms, so it is a good idea to refrain from swimming a couple days following rain. Caution should also be exercised when swimming in tributaries to the Huron, especially Honey Creek.

How are bacteria levels measured?

E. coli levels are monitored at specific locations in the watershed on a regular basis. All designated swimming beaches across the state are required to test waters for bacteria levels on a daily basis during the swimming season. Information on swimming beaches can be found at the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) BeachGuard website. In addition, the EGLE department samples a range of randomly selected sites once every five years to identify potential problem areas in the watershed. Finally, HRWC employs both volunteers and staff to routinely sample streams for E. coli levels at sites throughout the watershed, both in the main stem and in the tributaries, from April through September. Water samples are collected and sent to a lab, where lab staff determine a count of E. coli colonies.

If a persistent elevated levels of E. coli emerge through general sampling, Bacterial Source Tracking (BST) can be used to help determine the species of E. coli present and thereby narrow the scope of possible sources of the contaminant. BST uses genetic identification techniques and is more expensive than general monitoring, so it is only used after a potential problem has been identified.

Sources of bacterial contamination and what can be done