New plan sets recommendations to achieve healthy water

One of HRWC’s primary programs over the decades has been writing and facilitating the implementation of watershed management plans (WMPs). These WMPs set goals and recommendations to maintain and restore water quality across a particular land and water area. No individuals or organization can do this alone, as watersheds pay little heed to political boundaries. WMPs are developed with the input of multiple agencies, communities, organizations, and individuals, and only by working together can these groups implement WMPs and achieve success.

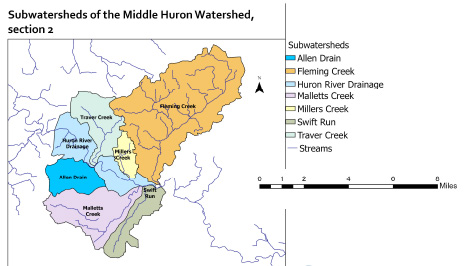

In November 2020, after three years of data collection and analysis, stakeholder meetings and report writing, the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency and Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) approved the WMP for the Middle Huron River, section 2. This area is composed of the Huron River from Barton Pond to the confluence of Huron River and Fleming Creek, and the land area draining water into the Huron through this section, including Allens, Fleming, Malletts, Millers, Swift Run, and Traver Creek creeksheds. Nearly all the City of Ann Arbor is contained in these watersheds, as well as parts of Ann Arbor, Salem, Superior, and Pittsfield townships. The area is fully contained in Washtenaw County.

To prepare the recommended actions to achieve the goals for the WMP, HRWC and stakeholder organizations for the region compiled a list of best management practices that would address the priority impairments of the region and be most feasibly implemented. The following list is not comprehensive but includes those determined to be highest priority. To see all recommendations and data, check out the full WMP at https://www.hrwc.org/what-we-do/programs/watershed-management-planning/middle-huron-WMP-section-2/.

1.Implement a Green Stormwater Infrastructure strategy and program. HRWC developed a process to incorporate available geographic, aerial and other remotely collected information to identify opportunities for Green Stormwater Infrastructure (GSI) projects to capture and infiltrate stormwater. A number of GSI projects and programs already exist in the watershed, but many more opportunities exist. A watershed-wide program or a program within each municipality is needed to incorporate GSI retrofit designs along key roads, publicly owned properties, and large business properties. Municipalities should also commit to installing GSI during major street replacement.

2.Targeted stream channel restoration. Over the past two summers, HRWC has conducted extensive stream surveying using the Bank Assessment for Non-Point Source Consequences of Sediment (BANCS) methodology to identify badly eroding channel sections in need of restoration. HRWC located 8 channel sections that are experiencing extremely fast erosion and need to be stabilized within the next several years to prevent excess sedimentation and habitat impacts downstream.

3.Enforce restrictions of new discharge permits. A total maximum daily load (TMDL) plan from EGLE concludes there is excess phosphorus entering Ford and Belleville Lakes, and it sets targets for limits on discharge permits. It is imperative to the success of all the phosphorus reduction activities going forward that no new sources be added to counteract these nutrient reduction efforts. HRWC and partner agencies commit to participate fully in public response to new permit applications. In this public response, the partners will request that EGLE uphold the goals of the TMDL by rejecting any new source permits.

4.Implement stormwater management plans. Municipalities in the watershed, along with the Washtenaw County Water Resources Commissioner and the Washtenaw County Road Commission, Ann Arbor Public Schools, and the University of Michigan all have stormwater plans that direct them on how to control and manage the quality and quantity of stormwater flowing through and out of their systems. These stormwater systems require inspections and maintenance. The municipalities need to enforce rules, standards, and ordinances for stormwater management on new and existing developments.

5.Implement the Public Education Plan. Governments and nonprofit leaders need help from everyone to achieve clean water in our waterways, and to do that, citizens need to know what specific actions they can take. Watershed partners have developed a Public Education Plan that includes 22 activities and strategies to address nine stormwater topics; it serves as guide for what organizations should highlight when teaching the public how their actions impact water quality.

6.Conduct bacterial source identification, remediation, and education. Bacterial pathogens following heavy rainstorms are a known issue in this watershed region. By utilizing targeted water sampling, genetic analyses, and canine source detection (bacteria-sniffing dogs!), HRWC and partners will be able to determine the presence and sources of bacteria in the watershed and target them for elimination. Furthermore, it is important to teach citizens how their actions (or lack thereof) related to septic system maintenance and pet waste disposal can affect water quality.

7.Develop a best practice strategy for de-icing. The river and tributaries in the watershed have consistently high conductivity levels, which can be highly correlated with chloride (Cl-) and sodium (Na+) levels and negatively correlated with biodiversity. Much of this can be traced back to winter use of road salt. There needs to be a concerted effort to develop and test de-icing procedures that will minimize impact to aquatic ecosystems.

8.Develop detention pond evaluation, maintenance, and retrofit procedures. Since the development of modern stormwater management guidelines, municipalities have built dozens of stormwater detention ponds throughout the watershed. Unfortunately, anecdotal evidence and pond surveys suggest that very few are getting the maintenance they need. Unmaintained detention ponds get clogged with sediment and lose their ability to treat the stormwater they capture. The WMP calls for an aerial survey of these ponds, followed by a strategy to continue maintenance to improve overall function.

9.Implement creekshed plans (Malletts Creek Strategy, Millers Creek Sediment Accumulation Study). Millers and Malletts creeks have been sources of sediment and flashy flows for decades, and these creeks in particular need continued management and restoration. In Millers Creek, a 2013 sediment study recommended several activities to reduce polluted runoff rushing into the Creek after storms. While partners have completed some of these activities, there is more to do. Similarly, many projects have been conducted in the Malletts Creekshed in the last ten years, resulting in noticeable improvements to the creek’s water quality. The WMP recommends continued action in Malletts and Millers creeks to keep up the strong momentum developed here.

10.Natural areas protection. Preserving natural areas is of utmost importance. The ecosystem services they provide moderate water flow, filter polluted runoff before it reaches waterways, and protect habitat for a wide range of plant and animal species. Land protection programs include the City of Ann Arbor’s Greenbelt program, Scio, Ann Arbor, and Webster townships’ land preservation programs, and Washtenaw County’s Natural Areas Protection Program. All of these programs are funded through land protection millages levied on property taxes, and these programs must continue. Other laws and policies can protect natural areas as well, like natural features protection ordinances and regional planning to direct development away from important natural areas.

Implementing these WMP project activities over the next ten years will result in the elimination or significant reduction in water impairments that currently bedevil the watershed. Improving ecosystems is not easy. It takes concerted effort over long time scales, but a plan provides all of us a roadmap to get there.