It’s time to celebrate and protect a law that transformed American waters for the better!

Fifty years ago, the Clean Water Act became law in the United States. It’s hard to express how critical it was to making waters safe for people and wildlife. The law was ambitious; it set a goal to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters.” It required polluters to acquire permits before dumping many types of waste. It dramatically increased federal support for municipal sewage treatment, and it empowered communities to hold polluters accountable.

Remembering how bad it was

In 2022, it’s easy to forget just how dirty rivers, lakes, and streams were before the Clean Water Act. Municipalities and companies routinely dumped raw sewage and untreated industrial waste into rivers and wetlands. Mainstream society saw creeks and lakes as little more than drains and dumps, commodities to be used and consumed for profit. Across Michigan and the country, people can share memories about polluted, abused rivers in their own backyards. The Huron River, where it ran through industrial areas, commonly smelled of chemicals and sewage, and it was frequently covered in oily sheens. Downriver from the Peninsular Paper Mill in Ypsilanti, the water often changed color depending on what dyes the mill was using. Kids were told not to let their clothes touch the river for fear that they may be permanently stained.

Before the Clean Water Act took effect, many rivers across the United States would literally catch fire. The Rouge River, right next door to the Huron, and the Cuyahoga River, which runs through Cleveland, both notoriously caught fire for the last time in 1969. The Cuyahoga Fire sparked a nationwide debate that is credited with giving the Clean Water Act momentum in Congress. It was a tragic, visible example that elevated environmental destruction in the public consciousness.

Collective action and champions made it possible

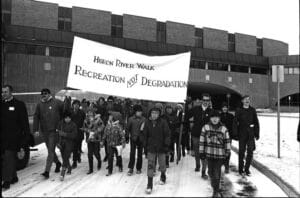

Many U.S. Senators and Congressional representatives from both major political parties deserve credit for passing the Clean Water Act, including two from Michigan: Congressman John Dingell, who was one of the bill’s architects, and Senator Philip A. Hart, who championed the vital connection between the health of rivers and the health of Michigan’s economy. But without persistent public demand and organized advocacy, the Clean Water Act never would have become law. HRWC and grassroots groups from all over the watershed lobbied local, state, and federal officials to protect waterways. Over several years, and as a part of a broader national movement, they saw their goals realized in one of the most comprehensive environmental statutes created to date.

Today, it might seem unbelievable that such a fundamental right as clean water would need such support, but major industries and powerful political forces opposed the act, just as many of those same groups oppose action to address climate change now.

Supreme Court could weaken the Clean Water Act

Since the passage of the Clean Water Act, special interest groups have succeeded in weakening specific parts and methodologies of the Clean Water Act. Just recently, in April 2022, the Supreme Court sided 5-4 with a Trump administration rule change that limits how states could protect waterways from projects like pipelines. The Court proceeded in an unusual way, using the so-called “shadow docket”, meaning they didn’t follow long-standing traditions and precedents for explaining their ruling. In fact, the majority issued no opinion despite objections from the minority justices. Furthermore, the law could face its most dire challenge yet in the Supreme Court during the upcoming fall term. The Court will hear arguments that could significantly weaken the law in ways long sought by real estate developers, construction associations, and industrial corporations.

The Court could determine the test that lower courts should use to define what constitutes the “waters of the United States,” or “WOTUS,” designation, which accords Clean Water Act protections. Many environmental experts agree that the case before the Court highlights flaws in the EPA’s methodology, and the administration is currently rewriting the rules governing the WOTUS. The cause for concern, however, is that the Supreme Court could broadly limit the Clean Water Act in ways that prioritize private corporate profits over the health of people and the environment. With fewer water bodies or groundwater sources defined as WOTUS, the Clean Water Act becomes significantly less effective.

Advocates for strong waterway protections understand that waters of the United States are connected through natural barriers like sandy dunes, porous soil, or natural springs. These types of invisible connections are common throughout the Huron River watershed. To protect our rivers and lakes, we also need to protect the groundwater that is connected to them.

A Strong Clean Water Act has been essential to a healthy Huron River

Clean water is sacred to the Huron River watershed, to Michigan, and throughout the Great Lakes region. Water is part of our identity. It’s who we are. Our ecosystem relies upon it, and we rely upon that healthy ecosystem. Looking over the past 50 years, we have plenty of reason to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act. Significant threats to waterways remain, but our waters are in far, far better condition than they once were, and much of that improvement originated with the Clean Water Act. Let’s commit to never taking clean water for granted. Join us in recognizing the benefits the Clean Water Act provides and in advocating for its continued standing as a foundational pillar of environmental protection.

—Daniel Brown

This blog post was originally published in the Huron River Report, Summer 2022.