PFAS were found in every fish tested throughout select locations in the Huron and Rouge River watersheds.

Last year, the Ecology Center’s Healthy Stuff Lab, with the support from HRWC and the Friends of the Rouge River, sampled fish from both rivers for a community-based study. Local anglers collected the fish, which were analyzed for 40 different PFAS chemicals.

PFAS were found in all fish tested, at levels generally consistent with what previously state-collected samples indicate.

This study differed from most other PFAS fish studies because it examined the whole fish, not just the filets, providing a better reference for what natural predators that eat the whole fish would ingest. The findings show significantly higher average PFAS levels in organs than in filets.

Finding More PFAS in More Places

We now know that fish located in distant or presumably safe areas from known, high-volume sources of PFAS also have high levels of PFAS in some of their organs.

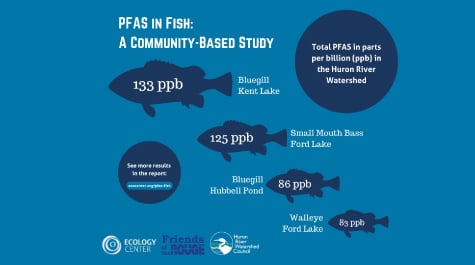

Kent Lake is located in the Upper Huron River, just downstream from Tribar Technologies, the major source of past PFAS contamination. Fish from Kent Lake contained high PFAS levels, up to 133 parts per billion (ppb). This is not surprising given its proximity to Tribar. However, fish collected from Ford Lake, which is much farther downstream near Ypsilanti, have PFAS levels of 125 ppb, while areas farther upstream had lower levels of PFAS in fish. We’d expect fish closer to major contamination sources to have higher levels of PFAS in their system, but that wasn’t always the case, nor was there a clear relationship between the level of contamination and the species of fish.

Furthermore, even waterways with no known sources of PFAS—those in relatively protected circumstances—have PFAS-contaminated fish. Whitmore Lake, for example, is not connected by the Huron River via surface water. There is no known source of PFAS nearby, and the levels of PFAS found in the lake water are low. Whitmore Lake was intended to be a “safe” reference lake in the sampling, serving as a control in the experiment, yet fish were found there with up to 22 parts per billion of PFAS. Locations connected to Portage Creek, near Pinckney State Recreation Area shared a similar result. Even fish in waterways surrounded primarily by protected park lands and some residential development contain PFAS. This all speaks to how widespread these “forever chemicals” have become. Since some lakes in protected and residential settings are affected, we can no longer assume isolated lakes are safe from PFAS.

Fish Could be a Major Source of PFAS Exposure for People Who Eat Wild Fish

In Southeast Michigan, some people rely on wild-caught fish for sustenance, and fishing and eating wild fish is an important part of many people’s cultural identity.

PFAS bioaccumulate in protein-rich fish tissue, and fish immersed in PFAS-contaminated water are constantly exposed to the chemicals throughout their lifetime. That means PFAS build up to high levels in fish and consuming the meat can deliver a high dose in one meal.

This Ecology Center report was finishing up just as a separate study from the Environmental Working Group showed widespread contamination in fish across the United States. The EWG study estimated that eating just one fish with the study’s median concentration of PFOS was equivalent to drinking water for a month contaminated at 2,400 times the EPA’s 2022 interim health advisory level.

PFAS Are More Toxic and More Widespread Than Previously Thought

The EPA released updated health advisory levels in June 2022, confirming that some PFAS are more than 1000 times more than previously thought. In 2021, the Centers for Disease Control found that PFAS are found in the blood of 97% of Americans. Other studies have found PFAS in Great Lakes rainwater, on Mount Everest, in different animal species around the globe, and in remote locations like the Arctic.

Putting all these pieces together, we can see some clear, alarming trends: PFAS are far more toxic and far more pervasive in the environment and our bodies than previously understood. That puts more people, wildlife, and ecosystems at greater risk.

PFAS Could Put Michigan Fisheries at Risk

These trends make me increasingly concerned about the safety of wild-caught fish and the State of Michigan’s fish consumption guidelines. In the Ecology Center study, the fish filets sampled showed at least one of 14 different PFAS chemicals present in every fish, ranging from 11 to 133 ppb. The state of Michigan currently regulates only two of the 14 types of PFAS discovered. The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) issues a “Do Not Eat” consumption advisory if PFOS in fish filets exceed 300 ppb but does not consider other PFAS chemicals for these advisories. Consequently, the total amount of PFAS in fish is very likely underrepresented by State reports, and the threshold level the State uses is based on obsolete information that doesn’t adequately express how toxic PFAS chemicals are. It’s plausible that if updated PFAS information from the EPA and other sources were incorporated into new Eat Safe Fish guidelines, no inland fish caught in the state of Michigan would be categorized as safe to eat.

These trends make me increasingly concerned about the safety of wild-caught fish and the State of Michigan’s fish consumption guidelines. In the Ecology Center study, the fish filets sampled showed at least one of 14 different PFAS chemicals present in every fish, ranging from 11 to 133 ppb. The state of Michigan currently regulates only two of the 14 types of PFAS discovered. The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) issues a “Do Not Eat” consumption advisory if PFOS in fish filets exceed 300 ppb but does not consider other PFAS chemicals for these advisories. Consequently, the total amount of PFAS in fish is very likely underrepresented by State reports, and the threshold level the State uses is based on obsolete information that doesn’t adequately express how toxic PFAS chemicals are. It’s plausible that if updated PFAS information from the EPA and other sources were incorporated into new Eat Safe Fish guidelines, no inland fish caught in the state of Michigan would be categorized as safe to eat.

The studies reveal so many implications, it’s hard to know where to begin. How should these results inform fish consumption recommendations for people that rely on fish for nutrition? Or for people who fish as important part of their cultural identity? How will they affect the traditions, heritage, and nutrition of Indigenous people, who have fished Michigan Waters for millennia? How could it affect the fisheries of the Great Lakes states, tourism, and recreation?

We Need the EPA and State Agencies to Help Us Understand the PFAS Risks We Face

The Ecology Center study, along with other recent studies from around the world, demonstrate why the EPA and the State of Michigan need to close gaps in our understanding about how PFAS enter our waterways, how they accumulate in fish, and how the toxic chemicals move through our ecosystems and our bodies. Right now, we have more questions than answers. We simply don’t have enough information to know how widespread the risk is, how variable PFAS levels are in fish populations, or what that means for the health of people and wildlife that eat fish.

Anglers Should Eat Safe Fish

Michigan has over 11,000 lakes, streams, and rivers. Unfortunately, many of those water bodies have been polluted with chemicals from mercury to PFAS, and its easy to lose track of what fish are safe and where. Be sure to consult the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Eat Safe Fish Guides before you go fishing.